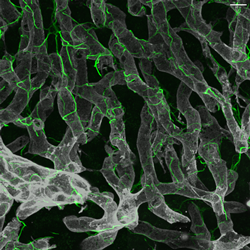

Hepatic stellate cells along with their intricate cellular projections (green) are shown wrapped around blood vessels (gray) in the healthy liver.

NEW YORK (PRWEB)

January 05, 2023

Using the latest technologies—including both single-nuclear sequencing of mice and human liver tissue and advanced 3D glass imaging of mice to characterize key scar-producing liver cells—researchers have uncovered novel candidate drug targets for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The research was led by investigators at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Utilizing these innovative methods, the investigators discovered a network of cell-to-cell communication driving scarring as liver disease advances. The findings, published online on January 4 in Science Translational Medicine, could lead to new treatments.

Characterized by fat in the liver and often associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and elevated blood lipids, NAFLD is a worldwide threat. In the United States, 30 to 40 percent of adults are estimated to be affected, with about 20 percent of these patients having a more advanced stage called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, which is marked by liver inflammation and may progress to advanced scarring (cirrhosis) and liver failure.

NASH is also the fastest-rising cause of liver cancer worldwide. Since advanced stages of NASH are caused by the accumulation of fibrosis or scarring, attempts to block fibrosis are at the center of efforts to treat NASH, yet no drugs are currently approved for this purpose, say the investigators.

As part of the experiments, the researchers performed single-nuclear sequencing in parallel studies of both mouse models of NASH and human liver tissue from nine subjects with NASH and two controls. They identified a shared number of 68 pairs of potential drug targets across the two species. Furthermore, the investigators pursued one of these pairs by testing an existing cancer drug in mice as a proof of concept.

“We aimed to understand the basis of this fibrotic scarring and identify drug targets that could lead to new treatments for advanced NASH by studying hepatic stellate cells, which are the key scar-producing cells in the liver,” said senior study author Scott L. Friedman, MD, Irene and Dr. Arthur M. Fishberg Professor of Medicine, Dean for Therapeutic Discovery, and Chief of Liver Diseases at Icahn Mount Sinai. “In combining this new glass liver imaging approach—an advanced tissue clearing method that enables deep insight—along with gene expression analysis in individual stellate cells, we have unveiled an entirely new understanding of how these cells generate scarring as NASH advances to late stages.”

The researchers discovered that in advanced disease, stellate cells develop a dense network, or meshwork, of interactions among themselves that facilitate these 68 unique interaction pairs not previously identified in this disease.

“We confirmed the importance of one such pair of proteins, NTF3-NTRK3, using a molecule already developed to block NTRK3 in human cancers and repurposed it to establish its potential as a new drug to fight NASH fibrosis,” said first author Shuang (Sammi) Wang, PhD, an instructor in the Division of Liver Diseases. “This new understanding of fibrosis development suggests that advanced fibrosis may have a unique repertoire of signals that accelerate scarring, which represent a previously unrecognized set of drug targets.”

The researchers hypothesize that the circuitry of how cells communicate with each other evolves as the disease progresses, so some drugs may be more effective earlier and others at more advanced stages. And the same drug may not work for all stages of disease.

The investigators are currently working with Icahn Mount Sinai chemists to further optimize NTRK3 inhibitors for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Next, the investigators plan to functionally screen all candidate interactors in a cell-culture system, followed by testing in preclinical models of liver disease, as they have done for NTRK3. In addition, they hope to extend their efforts to determine if similar interactions among fibrogenic cells underlie fibrosis of other tissues including heart, lung, and kidneys.

The paper is titled “An autocrine signaling circuit in hepatic stellate cells underlies advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.”

Additional co-authors are: Kenneth Li (Icahn Mount Sinai); Eliana Pickholz Li (Icahn Mount Sinai); Ross Dobie (University of Edinburgh, UK); Kylie P. Matchett (University of Edinburgh, UK); Neil C. Henderson (University of Edinburgh, UK); Chris Carrico (Gordian Biotechnology, CA); Ian Driver (Gordian Biotechnology, CA); Martin Borch Jensen (Gordian Biotechnology, CA); Li Chen PharmaNest, Inc., NJ); Mathieu Petitjean (PharmaNest, Inc.,NJ); Dipankar Bhattacharya (Icahn Mount Sinai); Maria I. Fiel (Icahn Mount Sinai); Xiao Liu (University of California); Tatiana Kisseleva (University of California); Uri Alon (Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel); Miri Adler (Yale University School of Medicine, CT); Ruslan Medzhitov (Yale University School of Medicine, CT).

The work was supported, in part, by funds from the National Institutes of Health grant numbers R01DK56621, R01DK128289, TR004419, P30CA196521, R01DK101737, R01DK099205, R01DK111866, R01AA028550, P50AA011999, P30 DK120515, and U01AA029019.

-####-

About the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is internationally renowned for its outstanding research, educational, and clinical care programs. It is the sole academic partner for the eight-member hospitals* of the Mount Sinai Health System, one of the largest academic health systems in the United States, providing care to a large and diverse patient population.

Ranked 14th nationwide in National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding and among the 99th percentile in research dollars per investigator according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, Icahn Mount Sinai has a talented, productive, and successful faculty. More than 3,000 full-time scientists, educators, and clinicians work within and across 34 academic departments and 35 multidisciplinary institutes, a structure that facilitates tremendous collaboration and synergy. Our emphasis on translational research and therapeutics is evident in such diverse areas as genomics/big data, virology, neuroscience, cardiology, geriatrics, as well as gastrointestinal and liver diseases.

Icahn Mount Sinai offers highly competitive MD, PhD, and Master’s degree programs, with current enrollment of approximately 1,300 students. It has the largest graduate medical education program in the country, with more than 2,000 clinical residents and fellows training throughout the Health System. In addition, more than 550 postdoctoral research fellows are in training within the Health System.

A culture of innovation and discovery permeates every Icahn Mount Sinai program. Mount Sinai’s technology transfer office, one of the largest in the country, partners with faculty and trainees to pursue optimal commercialization of intellectual property to ensure that Mount Sinai discoveries and innovations translate into healthcare products and services that benefit the public.

Icahn Mount Sinai’s commitment to breakthrough science and clinical care is enhanced by academic affiliations that supplement and complement the School’s programs.

Through the Mount Sinai Innovation Partners (MSIP), the Health System facilitates the real-world application and commercialization of medical breakthroughs made at Mount Sinai. Additionally, MSIP develops research partnerships with industry leaders such as Merck & Co., AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, and others.

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is located in New York City on the border between the Upper East Side and East Harlem, and classroom teaching takes place on a campus facing Central Park. Icahn Mount Sinai’s location offers many opportunities to interact with and care for diverse communities. Learning extends well beyond the borders of our physical campus to the eight hospitals of the Mount Sinai Health System, our academic affiliates, and globally.

——————————————————-

- Mount Sinai Health System member hospitals: The Mount Sinai Hospital; Mount Sinai Beth Israel; Mount Sinai Brooklyn; Mount Sinai Morningside; Mount Sinai Queens; Mount Sinai South Nassau; Mount Sinai West; and New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai.